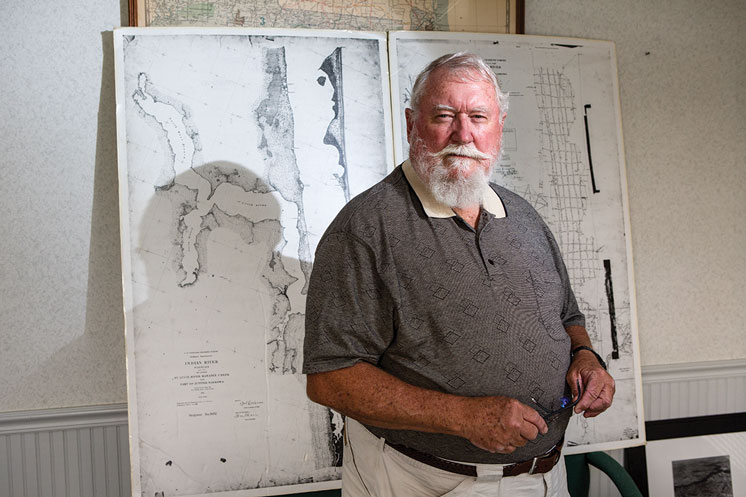

Through his surveying company, Chappy Young understands better than anyone the history and the nuances of the land and water that make up the Treasure Coast.

Chappy Young put the Everglades on the map—literally.

“I was trudging through that Sawgrass pulling a 200-foot tape to measure an Everglades parcel boundary back in 1965,” says the owner of GCY Surveyors and Mappers. “I’ve seen in many instances things come full circle.”

GCY was selected by U.S. Sugar and South Florida Water Management District in 2008 to survey U.S. Sugar land for the proposed purchase.

Young—widely recognized as owning and archiving the largest number of historical records on surveys and deeds in the Everglades—explains how land ownership and use was originally determined.

“The original 13 colonies did not have any public domain,” he says. “They had no federal government overseeing the land. The lands were either colony-owned or private. There was no public domain land.”

Later, federally acquired territories became public domain. Debate ensued over how best to use them. The conclusion? Sell them to private owners. Surveyors set the boundaries. Just one problem: “They did not know how to create a legal description in a deed given to a landowner because (the federal government) didn’t know how much land they had,” Young says.

Surveyors organized the land by sections, townships and ranges. Throughout the state, land offices sold property based on the surveys, transferring land from public to private domain. The feds deemed any land unfit for cultivation to the state.

“Federal surveying stopped at the margins of the large areas of swamp,” Young says. “That became wasteland in the eyes of the perspective of the time. We had a lot of swamp and overflow land. The largest of which, was the Everglades.”

At statehood in 1845, Florida acquired a half-million acres of swamplands. The Swamp and Overflowed Lands Act of 1850 obligated improving such lands for value. Further complicating that value potential, the federal government—land rich but cash poor—gave more than 2 million acres to the railroads for laying track. Its remaining land rose in value. The state’s use of swamplands was limited. Farming it, the preference, first commanded ditching, draining and digging canals—the precursor of the latticework system that redirects the flow of water today.

“Here we are today,” Young says, “blaming the farmer for turning the Everglades into farms.”

This has been an excerpt from Stuart Magazine. Read the full article HERE.